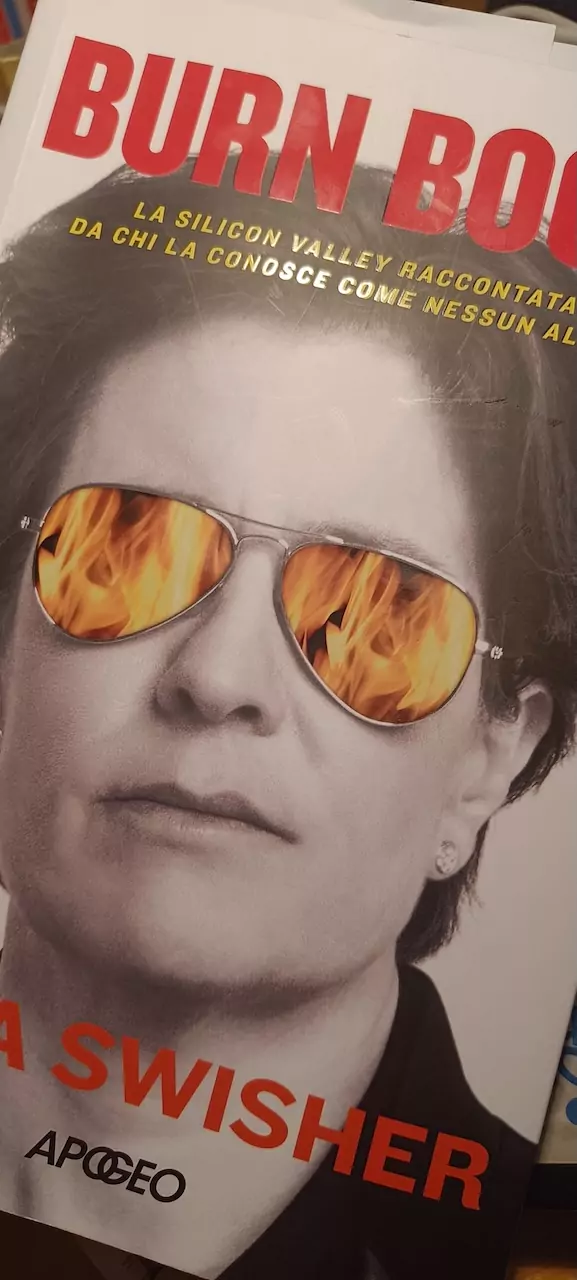

Kara Swisher is the journalist who has always chronicled Silicon Valley and the American tech industry. Kara Swisher has written a book called Burn Book (Apogeo, 222 pages, 25 euros), although the subtitle has been changed, which in the original version is ‘A tech love story’, and in the Italian version becomes ‘Silicon Valley told by someone who knows it like no one else’.

Swisher is sharp, pungent, empathetic, in-depth, describes, confronts, looks beyond the superficial, has traversed the events of the tech industry from the dawn of the internet to those of artificial intelligence, has written for prestigious newspapers such as the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal, has been an entrepreneur by founding All Things Digital and Code, platforms of information and journalistic dissemination dedicated precisely to the world of the tech industry. Above all, she has got to know all, but really all, of the protagonists of Silicon Valley’s history, she has delved into their relationships, she has looked into their souls, never settling for facade declarations.

Swisher’s book is not a book about technology, it is a book about humanity that has made technology its mission, it is a book about people and the first of the people the author tells is herself and she does so not out of a narcissistic urge but because she is aware that only by sharing her personal story with the reader is it also possible to convey her, equally personal, experience of meeting the many characters she tells about in the book.

There are the big entrepreneurs: Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg up to Reid Hoffman, Jerry Yang, Sergey Brin, Larry Page, Sam Altman and many others such as those of Uber, Zappos, Instagram, the great managers Sheryl Sandberg, Satya Nadella, Sundar Pichai, Tim Cook, the venture capitalists Marc Andreessen, Peter Thiel, the big bad guy who for Swisher is Elon Musk who over the years has turned into the worst version of himself, and then the good ones, the good ones starting with Dave Goldberg, Sandberg’s husband who died suddenly, and then also people from the entertainment world like George Lucas or Bob Iger, from politics, journalism.

The story flows following both a chronological logic, reserving some curiosities and perhaps lesser-known facts among those that have punctuated the evolution of the Silicon Valley epic, and a framework derived from the various human sensibilities that the author has encountered along the way. Swisher never entrenches herself behind half-truths, she never refuses to name names, she gets straight to the point and is impervious to the possible wrath of the tech-powerful who will read her story, she shows the deeper meaning of a journalistic approach, she tells it like it is, as she sees it, she argues reasoning and motivations, she talks about the good and the bad, she does not stop at partial judgements, she even invents a metric she calls ‘asshole-productivity ratio’ to give even more substance to her thought. She breaks out of the trap of the illusion that tech entrepreneurs do things to improve the world by reiterating from time to time that it is money at the end of it all that is the real driving force, she tells how the most widespread sentiment among the tech elite is that of victimhood, along with insecurity and loneliness, and how, not infrequently, adherence to political power has helped keep the American tech industry almost immune to restraining actions by US governments, something that, for example, Europe has not done because it is more attentive to consumer and citizen protection.

The book is a journey that intrigues both those who are curious to learn more about how the tech industry got here, and to get to know the backgrounds and humanity of the people who built and sometimes damaged the tech industry, taking mythological or idealised visions out of the field but going into the ganglia of an industry that, like all things human, is not all gold and glitter.

The book is also a little lesson in journalism, Swisher confesses, she tells how he has resisted the temptations of ultra-million dollar offers in order to maintain his independence, she tells how she has always had an analytical, investigative, operational approach, she confesses what her sources have been in the most sensational scoops that have studded her professional history, and how, at times, she has made courageous choices in order not to create an ambiguous relationship between his profession and her personal life. How there is much more information a good journalist gathers than he or she publishes, and how this information should only be published if it is relevant in the context of the story one wishes to tell, and not if it has little or no relevance but could prove harmful to someone. Above all, the author’s experience in finding the balance between journalistic independence and the desire to create her own publishing enterprise is illuminating, coining the figure she defines as ‘reporters’.

Today, Swisher lives in Washington DC with her wife and four children. She is still convinced that technology is a good thing, but she is also an advocate of the need to make it more compatible with the world, that it should be better regulated by, for example, taking away the power of big tech to dispose in every possible way of what she calls the database of human intentions, i.e. the information and actions of each one of us, and this is something that makes her deeply critical of US political institutions. She continues to watch with the same intuition that at the beginning of the internet era made her write that everything would be digitized, the continuous development of technologies starting with the possible evolutions of artificial intelligence.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©